2018 marks the centenary of (some) women getting the vote, and it sometimes feels like we still have a long way to go in the fight for equality. My colleagues Amy Towle, Amy Trend and Hannah Monkley expressed the same sentiment when they went to the Women’s March in January 2017 dressed as Suffragettes, with a banner that read “Same Shit, Different Century”. A picture of them subsequently went viral, and after being asked to appear at Port Eliot Festival to talk about the Suffragettes, they decided to start a podcast to share the stories they had discovered. Listening to the podcast, it’s been shocking to learn the extent to which women in this country endured police brutality, imprisonment and torture in their fight for the right to vote, but it’s also been fascinating to discover the savvy PR tactics employed by the Suffragettes to convey a striking and coherent message.

The Suffragettes’ colour scheme, devised by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, of green (for hope), white (for purity) and purple (for loyalty and dignity) is probably familiar to most of us, but they also advised members to wear the fashionable, feminine dress of the time (long skirts and high-necked lace blouses worn over corsets and petticoats). Author Cally Blackman describes how the colours were worn “as a duty and a privilege” and how effective they were at creating a striking spectacle when women turned out in their Suffragette “uniforms” in force. An edition of the Votes for Women newspaper in 1908 declared “The Suffragette of today is dainty and precise in her dress”, and Sylvia Pankhurst was aware that no one wanted to “run the risk of being considered “outré” and doing harm to the cause”.

I realised that (probably subconsciously, and to a lesser extent) I’ve been using the same thinking to inform my ethical fashion choices. Although I don’t follow every new trend, I always make an effort to look neatly styled in every outfit post, wearing carefully chosen clothes rather than just throwing on any old thing. When I started my blog I wanted people to see my approach to fashion as imaginative but accessible, and something that’s suitable for a wide range of lifestyles and social situations.

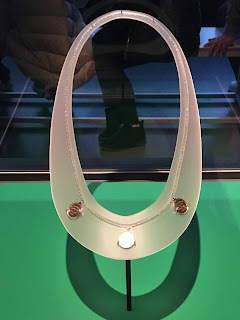

I find the ways in which femininity was performed and subverted by the Suffragettes really fascinating; I touched on the difficult relationship between femininity and feminism in a previous post about my love of vintage fashion. The jewellery in the Museum of London’s Votes for Women exhibition is an interesting microcosm of this. The medal awarded to Emmeline Pankhurst was in the style of military honours awarded to men, so this would have made a striking addition to a genteel outfit. The necklace awarded to Kitty Willoughby Marshall was a simpler design, featuring three coins on a delicate chain, and Louise Eates was awarded a beautiful Art Deco pendant. I love the thought that these were specially chosen to reflect the personal styles of these women, and to thank them for their unique contribution to the cause.

For the exhibition Suffragettes: Milennial Rebels milliner Claire Strickland recreated hats worn by prominent Suffragettes, and collaborated with photographer Nicholas Laborie to recreate portraits using young women as models. At a panel discussion about the exhibition, author Diane Atkinson raised a thought-provoking point. The large hats which were fashionable at the time, she explained, were a status symbol, and made the wearer look ladylike. Policemen sought to undermine this tactic by ripping the hats from Suffragettes during confrontations, to make them look dishevelled and slovenly. I found this description of violence quite disturbing, but it also showed how even a symbol of sophistication and elegance could be provocative if worn in the right context.

When we think of protest fashion now, we’re less likely to think of millinery, and more likely to think of T-shirts (my colleagues have turned their Instagrammable banner into a T-shirt and tote bag slogan to raise money for the charity Abortion Rights). T Shirts: Cult, Culture and Subversion at the Fashion and Textile Museum addresses some of the successes and contradictions of this simple but effective wearable tool of protest.

One of the best-known examples of a high fashion protest T-shirt is the oversized “58% DON’T WANT PERSHING” shirt made and worn by Katherine Hamnett to meet Margaret Thatcher in 1984. Hamnett has gone on to create T-Shirts protesting the Iraq War and fast fashion: her “No More Fashion Victims” T-shirt, made in collaboration with the Environmental Justice Foundation, is on display in the exhibition. This slogan isn’t just a neat play on words for Hamnett; she has campaigned against the use of forced labour in the cotton industry in Uzbekistan, and her T-shirts are made ethically from organic cotton.

It did make me question whether other slogan tees in the exhibition were just empty words; Dior’s “we should all be feminists” T-shirt looked fabulous, paired with their zodiac-embroidered maxi skirt, and a percentage of the sale price is being donated to the Clara Lionel Foundation (set up by Rihanna). However, the shirt itself retails at almost £500, and Dior’s parent company LVMH do not disclose any information about their supply chain.

Also featured in the exhibition was the “this is what a feminist looks like” T-shirt produced by the Fawcett Society, which was criticised for being sourced from a factory that did not pay a living wage. The exhibition addresses the environmental impact of making cotton t-shirts, and points out that “our consumer choices are social and political acts”. Two T-shirts from ethical brand Lost Shapes are on display, playfully illustrating two contrasting viewpoints for the conscious consumer.

I’m not a great T-shirt wearer (I prefer a slogan tote bag), but I have been thinking about how the contents of my wardrobe could be considered “protest fashion”. In her book “Folk Fashion”, Amy Twigger Holroyd explores the idea of refashioning or making clothes as a political act: “I am aiming, as much as I can, to disrupt the dominant paradigm of industrial production and overconsumption in fashion, and to contribute to the construction of an appealing alternative”. My friend Ludi, who took up sewing to make the sort of clothes that aren’t available in her size on the high street, had similar feelings in a post on Facebook: “I think learning to sew is body-positive and powerful and politically interesting”. I think I’ll be returning to this topic in a later blog post!

At a time when consumer culture is doing more harm than good, perhaps it’s once again to see our everyday clothes as tools we can use to campaign for the sort of world we want to live in. Making thoughtful, ethical choices instead of impulse purchases and rocking our vintage bargains and refashioned finery, we can start to turn the tide on overconsumption.

Thank you, I was excited to find your t-shirts at the exhibition! The Same Shit Different Century podcast has upcoming episodes on military tactics and "branding" (for want of a better word), and the podcast is full of fascinating information that I didn't know before.

ReplyDelete